THE city has been marking the 60th anniversary of the end of the Bristol Bus Boycott with a series of sixty events and commemorations, from inspiring artwork to services and community activities.

The boycott in 1963 was seen by many as a shocking part of Bristol’s history – but one that led to huge changes in racial equality in the UK.

It started after 18-year-old Jamaica-born Guy Bailey was refused a job as a driver with the Bristol Omnibus Company because he was black.

At the time it was legal to discriminate against someone because of the colour of their skin, and the bus operators had worked with the local white-dominated branch of the Transport and General Workers’ Union to ban Black and Asian people from becoming drivers and conductors.

Guy was one of about 3,000 people of Caribbean descent who had come to Bristol after World War II, when the country was desperate for more workers.

Another among them was Roy Hackett, who emigrated to the UK in 1952, and had already been turned down for a labouring job because of his colour when, in 1962, his wife Ena applied for a job as a bus conductor, and was refused.

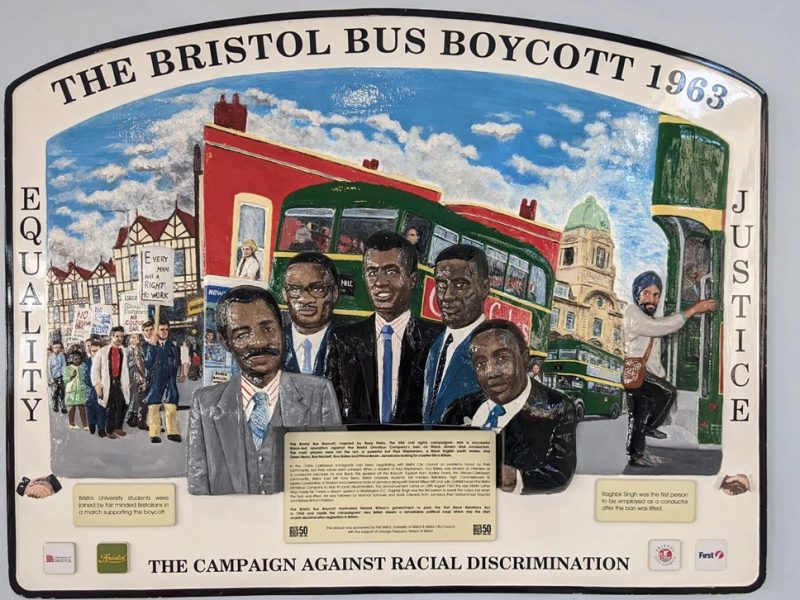

Hackett and several other St Paul’s residents including Owen Henry, Audley Evans and Prince Brown formed the West Indian Development Council to lobby for equal rights.

They were joined by Paul Stephenson, who arranged a bus driver job application for Guy Bailey. When Stephenson told the company that Bailey was West Indian, the interview was cancelled.

Inspired by the refusal of Rosa Parks to give up her seat on a bus in Alabama and the ensuing Montgomery Bus Boycott in the United States in 1955, the activists decided on a bus boycott in Bristol.

In April 1963, the WIDC started a boycott of all the company’s bus services across Bristol – and Bristolians from many different ethnic backgrounds joined in.

To illustrate the parallels with the 0American civil rights protests, local photographers were invited to follow Owen Henry on to a Bristol bus. Pointedly, Henry stood at the back.

The boycott finally ended on August 28, 1963 – the day of Martin Luther King’s historic ‘I have a dream’ speech, when Bristol Omnibus Company backed down and overturned its discriminatory ‘colour bar’ policy.

Three weeks later, on September 17, Raghbir Singh, a Sikh, became Bristol’s first bus conductor of colour. Shortly after, Norman Samuels became Bristol’s first Black bus conductor.

The success of the Bristol Bus Boycott is credited as paving the way for the UK’s Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1968, and is now at the heart of the Equality Act 2010, which legally protects people from discrimination in the workplace and in wider society.

Julz Davis of Curiosity Unltd, the organisation behind the 60th anniversary celebrations said: “In a year of many anniversaries, the boycott stands head and shoulders above them all.

“No other city in the world can say when Rosa Parks sat down Bristol stood up and marched for equality or that on the day the city defeated the colour bar, Martin Luther King Jnr had a dream.

“Building on this legacy, we look forward to coming up with new and innovative ways to address and accelerate racial justice for all, for good.”

Stephenson, Bailey and Hackett were all awarded OBEs for their part in the boycott.

Evans and Henry are two of the Seven Saints of St Paul’s and are honoured on murals in the area.